By Tiffany Hsu, Walter Hamilton and Chris O’Brien

Los Angeles Times

As millions of bargain-crazed customers swarmed through Target stores on Black Friday, one of the most audacious heists in retail history was quietly underway.

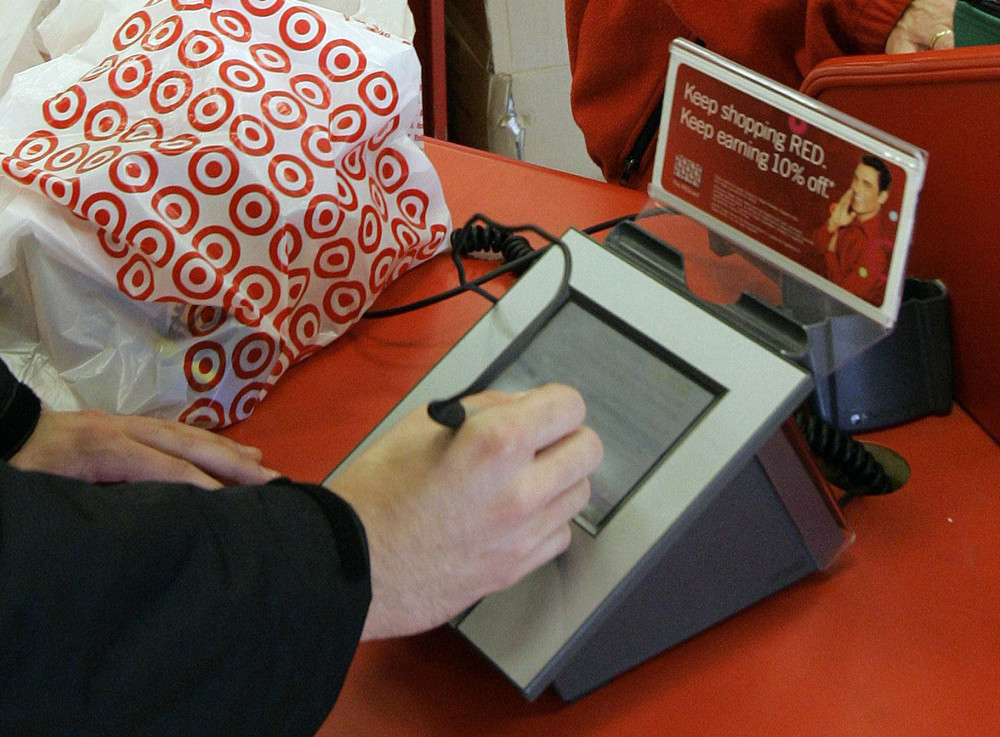

A band of cyberthieves pilfered credit and debit card information from the giant retailer’s customers with pinpoint efficiency as shoppers bought discounted sweaters and electronic gear on the unofficial launch of the holiday shopping season.

By the time the scheme was discovered, the unidentified hackers had made off with financial data of 40 million Target customers over a 2 {-week period. It ranks as one of the nation’s biggest retail cybercrimes on record.

Target disclosed the security breach Thursday, saying the thieves had purloined customer names, card numbers and a security code encrypted in the magnetic strip. The theft enables the culprits to make phony credit cards, make fraudulent purchases or siphon money from bank accounts.

The data breach underscored the evolving sophistication of cybercriminals and the persistent vulnerability of retailers and consumers despite dozens of past incidents at major retailers.

“How do you get 40 million credit cards and no one knows about it?” said Ken Stasiak, chief executive of SecureState, which investigates cybercrimes. “That’s a hell of a lot of credit cards. There should have been someone inside the company who spotted this much sooner.”

The Target attack appeared to be well thought out and executed with great precision.

The Minneapolis retailer said the hack occurred between Nov. 27, just before the annual holiday shopping frenzy, and Dec. 15. The breach affects people who bought goods at any of Target’s 1,797 stores nationwide, but doesn’t affect those who made purchases online.

In previous attacks against retailers, “skimmers” placed inside credit-card machines at checkout counters grabbed data from the cards’ magnetic stripes. Hackers have also targeted Wi-Fi networks that transmit data within stores.

The scope of the Target attack suggested that criminals might have gained access to encrypted customer information on a central database, security experts said. Another theory is that they sent malware-laden email to Target employees that spread through the retailer’s network once those emails were opened.

“Whoever did this is pretty sophisticated _ it’s most likely not some teenager sitting in his room,” said Peter Toren, a former prosecutor with the Department of Justice’s IP and Computer Crimes division.

Target didn’t give any details about how the scheme may have been carried out. The Secret Service said it is investigating. Banks and credit card companies rushed to assure customers that they would not be liable for any fraudulent transactions.

Customers who think they may be affected should scrutinize card statements and free online credit reports for suspicious behavior, experts said.

The Target fiasco could cost consumers $4.1 billion, almost all from potential debit card losses. Beyond that, victims collectively could spend as many as 131 million hours getting their accounts in order, according to Javelin Strategy & Research.

The theft of credit card data is a highly lucrative business. Criminals either manufacture counterfeit cards, resell the data on underground forums or make fraudulent online purchases themselves.

Corporate America has made progress in thwarting cybercrime, but many companies still devote insufficient money and resources, experts said.

“We’re seeing massive data breaches frequently due to low-hanging types of security problems,” said Andrea Matwyshyn, a University of Pennsylvania law professor who specializes in computer security. “Traditionally, questions of information security have been viewed by many companies as something that the IT department does, and that is a cultural mindset problem that is at the root” of some of the problems.

The heist intensified a debate about consumer privacy at a time when the value of personal financial information has skyrocketed.

Major businesses increasingly gather and analyze information about customer demographics and buying habits in a strategy known as data mining. The goal often is to personalize product pitches to reach customers more effectively.

“Personal data is king to merchants, to retailers, to banks, to the NSA and to organized-crime groups all over the world,” said Mark Rasch, an attorney and expert in computer security in Bethesda, Md.

Giant retailers and credit card payment processors have been frequent targets of cyberthieves.

This summer, federal officials said that a ring of Russian and Ukranian hackers stole 160 million credit card numbers targeting retailers such as JCPenney and 7-Eleven over several years and used the data to filch millions of dollars.

In 2007, T.J. Maxx and Marshalls parent company TJX Cos. said hackers had entered its computer systems _ where at least 45 million credit and debit card accounts were on file. The hackers had access to the system for more than a year before being detected.

TJX agreed in 2009 to pay $9.76 million to 41 states to settle an investigation of the breach.

The size and scope of the Target attack raised questions for many in the security community about how robust its defenses are and how vigilant the company is in terms of watching for clues that a breach had occurred.

The company may face consumer lawsuits and government fines “if it turns out that their security was lax and they were negligent,” said Toren, the former prosecutor.

Now that Target and authorities are on to the scheme, the culprits are likely to rush to capitalize on the stolen information. Shoppers making massive last-minute purchases before Christmas could discover a nasty surprise.

“The shelf life of those cards is down to days,” said Alex Moss, managing partner at security firm Conventus. “If consumers’ data was compromised, they could find their card balances maxed out very quickly, and then they’re stuck until the investigation is over. That could put a huge portion of people in a tight spot, particularly during the holiday season.”