By Thomas Lee

San Francisco Chronicle.

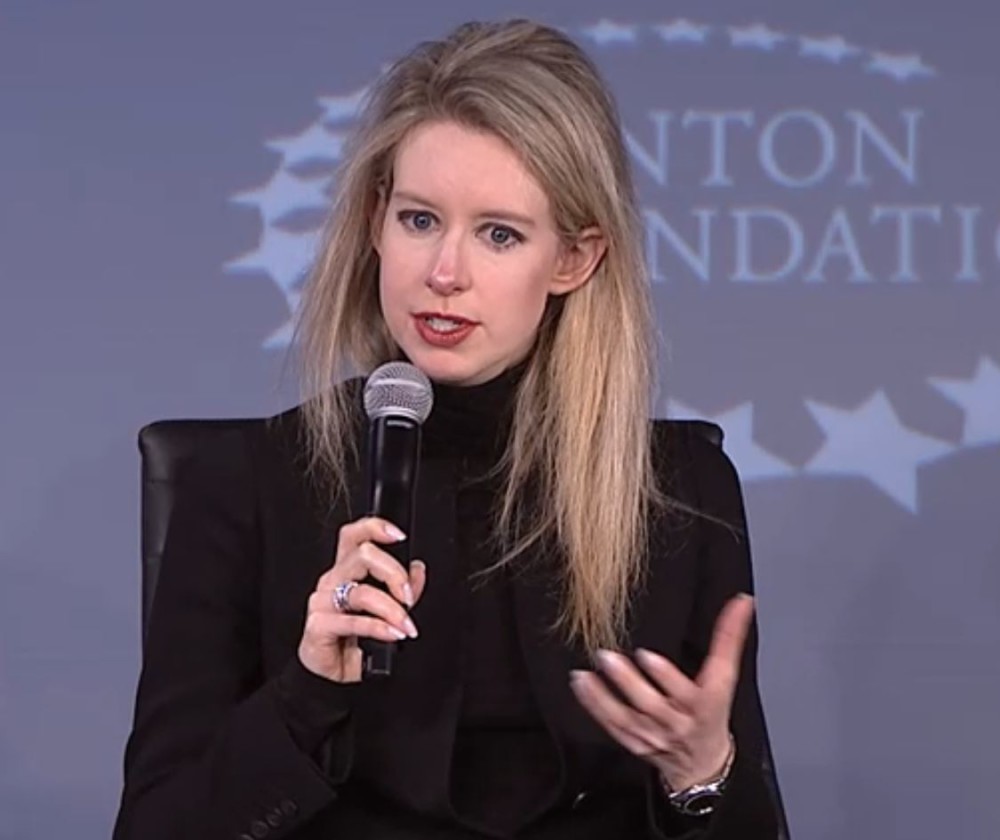

In early July, Theranos, the Palo Alto blood diagnostic startup founded by superstar entrepreneur Elizabeth Holmes, had some big news to share.

The Food and Drug Administration had granted 510(k) approval to Theranos’ testing system for herpes.

“FDA’s review process for 510(k) notifications is widely recognized as one of the most rigorous regulatory hurdles in the world for evaluation of the performance and accuracy,” the company said. “Today’s announcement demonstrates that Theranos has met that standard and is an important step in Theranos’ mission to … empowering individuals everywhere with information to live healthier lives.”

Given the breathless tone of the statement, you would think that Holmes had just won the Nobel Prize for Medicine. But it turns out 510(k) approvals are pretty standard in the medical device industry. And contrary to what Theranos suggested, 510(k) does not mean the agency has blessed the “performance and accuracy” of the company’s technology. It simply means that Theranos’ tests are pretty similar to a previously FDA-approved device on the market.

“The 510(k) clearance is not a determination that the cleared device is safe or effective,” according to an Institutes of Medicine report, commissioned by the FDA itself.

Founded by Stanford dropout Holmes when she was just 19, Theranos has promised to revolutionize health care by introducing a simple way to test for multiple diseases with one prick of the finger.

Holmes’ audacious vision has helped Theranos earn a $9 billion valuation, a superstar board of directors and glowing media coverage. But recent reports by the Wall Street Journal have cast doubt on whether Theranos’ technology really works.

The FDA sent Theranos several 483s, forms that cite flaws such as selling unapproved devices across state lines and not creating a proper system to handle consumer complaints.

In many ways, Holmes’ recent struggles demonstrate the inherent tension between Silicon Valley and older industries that startups like Theranos threaten to disrupt.

Until now, there has been a clear line between the software companies and gadget-makers of Silicon Valley and the medical world. Though both industries rely on new technologies, startups like Uber and Reddit can scale pretty fast while it can take a decade for medical device and drug companies to earn regulatory approval before they sell one product.

Theranos seems to straddle both worlds, not always comfortably. The company’s multibillion-dollar valuation and superstar status, things fairly common in Silicon Valley, are significantly at odds with the broader medical device community. Having covered the industry for several years in Minnesota, home to giants like Medtronic and St. Jude, I can tell you that most medical device firms are decidedly unglamorous and certainly don’t attract the money and attention Theranos does.

For example, the FDA’s 483 infractions are pretty common among medical device firms, though “companies need to take these observations seriously,” said Linda Bentley, who chairs the FDA practice group at Mintz Levin law firm in Boston. A 483 is still a long way from receiving a warning letter from the FDA, a much more serious situation, she said.

In other words, resentment may be driving much of the backlash against Theranos, something that Holmes seemed to suggest at the recent Fortune Global Forum in San Francisco.

“Much of what has been written is inaccurate,” Holmes said. “What did we do to get to this place?”

But Holmes bears much of the blame. She has promised no less than a health care revolution with her technology, pronouncements that are sure to attract scrutiny. And she seems to rely extensively on the FDA to back her claims — hence the big deal with the 510(k) announcement.

Holmes has now promised more transparency.

“We need to do a better job at communicating,” she said. “We have not put into the public domain the work we are doing. We need to get the data out there.”

Holmes has also displayed a surprising naivete about the process. For example, her board consists of big names like former Secretary of States George Shultz and Henry Kissinger, lawyer David Boise, and former Wells Fargo CEO Dick Kovacevich. What’s missing are people with expertise in FDA regulations, especially since the agency in recent years has taken a much closer look at newer diagnostic technologies, Bentley said.

When asked about the board at the Fortune forum, Holmes noted that Theranos also has a medical board. But such boards normally advise companies on the technology, not regulation.

And back to those 483s from the FDA. While fairly common, any self-respecting medical device company does not want them, a diagnostic startup CEO told me. And they hire the appropriate staff to ensure they don’t get them.

“You take great pride if you have an FDA inspection and don’t get a 483,” said Bill Pignato, a former top regulatory executive at Novartis and Genentech who runs a consulting firm in Boston.

Morever, Holmes needs to grow a little more into the CEO role. At the Fortune forum, she seemed to suggest Theranos’ problems have more to do with image than substance. In doing so, Holmes risks not understanding the severity of her situation.

“I’m definitely not a PR person,” she said.

That’s an odd statement, since Holmes has enjoyed tremendous publicity so far, appearing on the cover of Fortune, Forbes and Inc., which floated the idea that she could be the next Steve Jobs.

No, Holmes is a mighty good PR person. Just not the kind who can handle negative publicity.