Steve Johnson

Chicago Tribune

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) As Steve Johnson points out, live musicians were especially hit hard over the past 12 months, adding, “We have watched live popular music, once so vital and ubiquitous, dwindle to a smattering of mostly outdoor concerts with attendance limited by the space available.”

Chicago

The catalog of loss from 2020, even limiting the category to the arts, is a fat one.

A year ago this weekend, Chicago and the nation began rolling up the carpets and padlocking the doors in response to what was then a new threat but is now our intimate companion, insistent and inescapable.

COVID-19 came in on a whisper but it quickly became the heavy-metal soundtrack to everything.

And in the very long 12 months since that time, we have watched live popular music, once so vital and ubiquitous, dwindle to a smattering of mostly outdoor concerts with attendance limited by the space available.

We have seen moviehouses go dark for so long they don’t even smell like popcorn anymore, and we are left to wonder how many of them ever will again — a question that we must ask even now, as we clamor for the tantalizingly close promise of vaccination and relief.

Our live theater venues and classical music auditoriums transformed into great urban barns, warehouses for chairs that are, for some reason, numbered and lettered, lined up in regimented rows and all facing the same direction. Who can fathom this mystery?

The fact that our circuses have been mostly shut down may seem tangential to the bread that is real life. But as a segment of the economy, arts and culture blows away, for instance, agriculture in terms of the value it adds to the nation’s gross domestic product, according to a National Endowment of the Arts study.

The $878 billion contributed by the arts and culture sector — which includes not just filmmaking and performing arts but broadcasting, publishing and streaming — trailed only two others, healthcare and social assistance, and retail, according to the March 2020 report, which examined data up to 2017.

Arts and culture employment was on a steady upward curve throughout the 2010s, and Americans spent more than $26 billion on performing arts admission in 2017.

All of which is a number-heavy way of saying: The arts and culture are much more central to our lives, and much greater a loss when they are sidelined, than we probably realize. And if you could quantify their emotional impact, the way they soothe, instruct, provoke and bond us, their import would only rise.

The pandemic took arts makers themselves from us. With more than 600,000 dead in the U.S. and counting, there are of course marquee names on the list: the singer-songwriter John Prine, the playwright Terrence McNally, the fashion designer Kenzo Takada, the country singer Charley Pride, the jazz musician Ellis Marsalis, and on and on and on.

But as great a toll is being taken among the names you’ve never heard, all the stagehands and roadies and prop builders, the ticket takers and the makeup artists, the junior curators and the rhythm guitarists who were just starting to try some songwriting.

Some of them died, too, and some just got discouraged. These were people who loved working in the arts, who were willing to maybe get paid a little less and work a little less regularly to do so, but now have had no choice but to move on. The culture sector’s loss is, what, consulting’s gain? Retail’s?

We won’t ever be able to fathom the talent drain that is occurring, but all the statistics suggest it is profound.

“The stats are eye watering,” said John Featherstone, whose Lightswitch lighting design company helped organize the local contributions to the Red Alert protest, a late summer lighting of buildings in red to symbolize the crisis in the entertainment field and to advocate for government relief. “Seventy-seven percent of the people in the events industry have lost 100 percent of their income. Ninety-seven percent of 1099 workers in our business” — freelancers, essentially — “have lost their income altogether.”

That protest was in September. For months before and months after the live performance industry had to wonder if the nation — which in better times suggested it cared by buying those $26 billion worth of tickets — really did care all that much.

A “Save Our Stages” bill languished in Congress throughout most of 2020, only passing into law, finally, at the very end of the year. Even now, more than 2-\u00bd months later, the bill’s promised $15 billion in relief for shuttered venues across the arts realms is inaccessible. The federal Small Business Administration says it is still working to transform the legislation into actual grants that actual businesses can apply for.

Being left to twist like this while other industries get relief is enough to give an industry a complex. Maybe they just use us for the diversion we provide and are just fine with switching allegiances over to Netflix? Maybe when the dust settles and concert halls, say, can reopen, a would-be entrepreneur will look at what happened in 2020 and think, nah, instead of opening the rock club I always dreamed of, I’ll try something steady and stable instead, like a restaurant.

Speaking of restaurants, we are always losing and gaining them. (That was a joke about stability.) But since the pandemic, the closings have been rapid-fire. In its first six months, 80,000 Illinois restaurant workers lost jobs, according to the state’s restaurant association, and the running list the Tribune has kept of places shutting down is a chronicle of heartbreak.

The more famous names among the dozens of eateries now shuttered include the Michelin-starred Blackbird, the Chicago Ditka’s location, and Davanti Enoteca in Little Italy.

There’s lost opportunity of a more intangible kind, too. As museums through the past year have shut down, canceled exhibits and laid off staff, reopened at limited capacity, then shut down and reopened again, one museum director told me she wonders, how many kids didn’t visit and were denied that spark that gets lit by seeing a Monet on a wall or a Richard Hunt on a pedestal?

Similarly, how many might-have-been STEM workers will follow a different vocational path because they didn’t go to the Museum of Science and Industry this past summer?

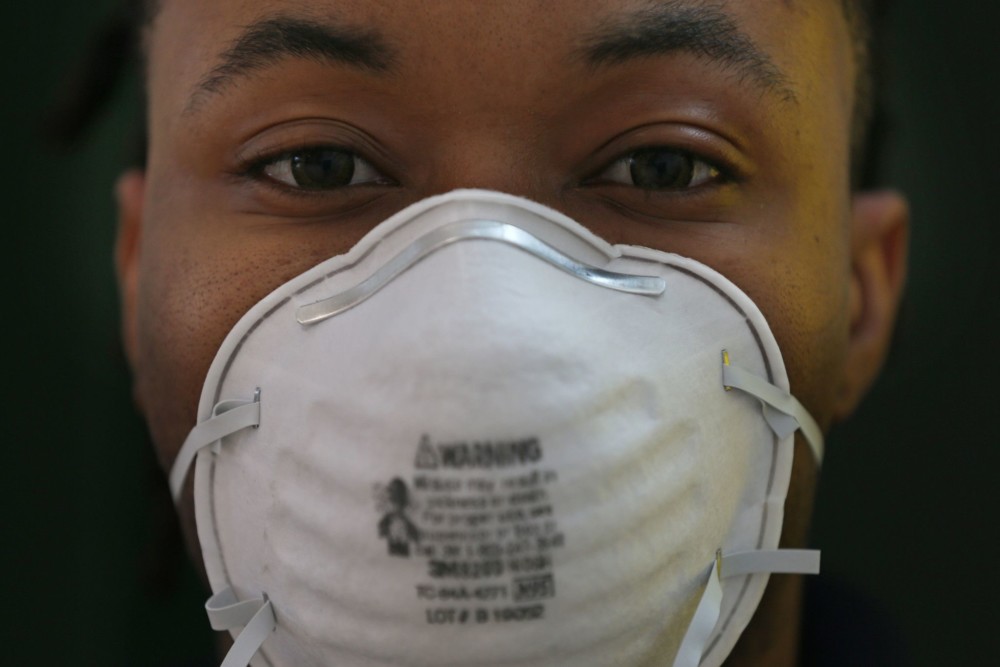

And then there’s a more generalized and more internalized kind of intangible. I would submit that we have lost in the last year our comfort, our sense of ease in the world. Maybe this swagger was unmerited, and we should have been wearing masks and worrying about even not-so-novel coronaviruses all along. Regular flu’s toll is pretty terrible, when you open your eyes to it.

But now, certainly, whatever happens with the coming year’s recovery, it’s going to be a challenge for a whole lot of us to eventually stand again like vertical cordwood at the Metro or a music festival, to sit next to a grand dame sucking on cough drops at the Lyric Opera. It’s tough to even contemplate being in the first scattering of people the city is allowing back into baseball games, spread out and in the open air.

Just as some of our Great Depression-era ancestors forever after had a hard time spending money on anything that was not essential, some of us who have lived through this pandemic won’t be able to shake visions of droplets spreading through the air and the deadly potential of communal human activity.

Or will most of us just forget?

Almost as scary as being damned to living in a kind of low-grade fear is the possibility that, as impactful as this last year has seemed, we might well slough off the very memory of it.

It happened before. “Influenza 1918,” the powerful look by PBS’s “American Experience” series at the last great pandemic, notes that this cataclysmic national event was very rarely addressed in subsequent decades in the creative arts.

It, too, was responsible for more than 600,000 American deaths in a relative flash of virality, and it was perhaps even more horrific for tending to favor people in their 20s as its targets.

Yet, says the program’s narrator, “as soon as the dying stopped, the forgetting began.” An epidemiologist surmises that it was just “so awful, so frightening” that people essentially erased it from memory.

A century later, we get a terrible do-over. Will we, too, roar through the ’20s, blithe and seemingly blindered? Or will we recognize and honor what was lost?

___

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.