By Kristina Davis

The San Diego Union-Tribune

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) In an effort to combat women leaving the law profession, the American Bar Association has launched an initiative to determine why women are leaving law firms — or saying goodbye to the profession altogether.

The San Diego Union-Tribune

For decades, roughly equal numbers of men and women have been graduating from ranked U.S. law schools. And for the first time last year, women outnumbered men in enrollment.

But, according to the American Bar Association, women make up only 36 percent of practicing attorneys.

So where are all the female lawyers?

They are leaving — many of them within five years of entering private practice.

When it comes to who is at the top, only 18 percent of equity partners at law firms are female.

“One of the reasons is there aren’t that many women left at that point,” Hilarie Bass, president of the American Bar Association, said in an interview during a recent visit to San Diego.

In an effort to combat the phenomenon, the American Bar Association has launched an initiative to determine over the next year why women at various stages in their careers are leaving law firms — or saying goodbye to the profession altogether.

Bass and other attorneys who have been studying the issue predict they know many of the reasons why women leave — discrimination, lack of work-life balance, childcare, success fatigue, sexual harassment.

And while these are issues that have challenged professional women for decades, experts are asking whether there is something unique to the law firm culture that makes it particularly unfriendly to female advancement.

They’ve heard the anecdotes. Women in their 50s who are at what should be the peak of their careers saying they feel invisible. Younger associates who complain they are given less interesting, more simplistic work than men and struggle to meet their billable-hour requirements. Women who feel they have to work harder to gain the same success as men and have reached burnout.

But, said Bass: “Anecdotes don’t change perceptions, data does.”

Once the study is completed, the association will come up with specific recommendations to keep more women lawyers practicing. The recommendations are expected to be announced at the association’s annual meeting at the year’s end.

“We’ll know we made progress when the average hardworking woman is as successful as the average hardworking man,” she added.

The Lawyers Club of San Diego, a professional organization dedicated to promoting women in law, is working on the issue, as well, by focusing its message on how women can rise to the challenge. Workshops this year will empower women to ask for what they deserve and encourage veteran female attorneys to mentor or sponsor younger ones.

While experts recognize the issue of retaining female lawyers crosses all types of law, much of the effort is focused on diversity in big law firms, which aren’t required to be as transparent about hiring and employment practices as government agencies.

Implicit bias

Much of the workplace gender gap — no matter what the profession — comes down to implicit bias, experts say.

Everyone to some degree harbors stereotypes that are so ingrained in us that we make decisions and assumptions based on them often without realizing it.

“It infiltrates everything,” said Bass, a top litigator in Miami. “In some ways, it’s almost more challenging to drum out. … Most people do not believe they have it. And when they are called out on it, they rationalize their behavior.”

Implicit bias is largely blamed for the pay gap between the sexes, and has been demonstrated in exercises that ask employers to choose between male and female candidates who present the exact same resumes.

In law firms, it translates to a male-heavy partner track, less interesting work for women and a harder road to meet the firm’s billable-hours requirements, female attorneys say. And when billable hours aren’t met, then performance evaluations suffer, as do raises and chances for promotion.

Sexual harassment is another reason women leave, and is likely the final straw in a long list of grievances, said San Diego attorney Olga Álvarez, president of the Lawyers Club.

Law firms provide fertile ground for such behavior, Álvarez said, with young female associates working with older male partners late at night, both far away from families. “This work schedule eats away at the professional environment,” she said.

Other partners may be hesitant to call out a colleague for such incidents for fear of losing a big moneymaker, and the victims don’t report it for fear of retaliation, she said.

Leaving

In the past, efforts were focused on retaining women who wanted to have children, and better maternity and part-time policies were put into place at many firms, experts said.

That hasn’t seemed to reverse the trend.

Elena Deutsch is a New York-based executive coach who specializes in women who want to transition from law firms to other careers, and she has plenty of clients. The name of her website says it all: womeninterestedinleavinglaw.com.

“Millennial women are more empowered to leave,” Deutsch said. Younger women are aware that a work-life balance is possible, and when they look at older women in their firms who are partners, they don’t like what they see.

“Once they get closer to being partner and look over the edge — I’ve had a client describe it as a snake pit — they don’t want to be that. They don’t see happy senior partners who are women.”

That was the experience of one San Diego attorney, who left a prominent local law firm — on good terms — when she decided she did not want to pursue a partner track, and she also wanted to develop her litigation experience quicker than she knew would be possible there.

“I worked all the time. I worked on my wedding day,” said the attorney, who the Union-Tribune is not naming to protect her privacy. “It was a hard life, and I wanted to stay married. It was partly my fault because I didn’t have boundaries, but you can’t really say no.”

She also didn’t see many female partners she wanted to emulate.

“There are two kinds of women attorneys, those who were treated like crap and aren’t going to treat anyone else like that, and women who are like, ‘I had to go through it so you have to go through it, too.'”

“It’s part of toxic masculinity that’s the culture of law.”

She moved to a few smaller firms — “I knew I was replaceable and that was communicated to me on a regular basis” — and was eventually wooed to a San Diego boutique practice by an attorney she knew and admired.

But she said promises of good compensation were empty. She was put on pro bono work and an insurance case that didn’t pay well.

She said at one point she stumbled on records of the billable hours of others in her firm and realized she was being paid less than the men despite having more billable hours. When she brought it up to her boss, she was fired.

“I left the practice of law for two years as a result of that,” she said.

She eventually came around, encouraged by her friends, and got into some light contract legal work before opening her own solo practice last year.

“I was delighted to discover I don’t hate practicing law,” she said. “I realize you can reshape the paradigm, it doesn’t have to be a big law firm run by white men.”

While the San Diego attorney didn’t exactly leave her firm voluntarily, other women who are looking for a change experience a big dose of guilt.

“If you go to law school, you are usually a go-getter, motivated, think of yourself as pretty tough and overall aren’t afraid of challenges,” said one female attorney in her 30s in Minneapolis who is looking to transition out of her firm. “Am I just quitting on something because it’s difficult? Or are there good reasons for me not to be doing this?”

The attorney is a client of Deutsch’s and agreed to speak with the Union-Tribune as long as she wasn’t identified.

“I think a lot of attorneys, especially women, struggle with billable hours. It’s a way productivity is measured by time spent rather than how you spend the time. … For me, it’s not conducive to quality work,” the Minnesota attorney explained. “At times I feel pressured to dip around in areas I don’t think serve the client’s best interest but get more time billed, or sometimes not bill for my time to make sure some things are super duper extra amazing, just to keep a client coming back.”

Invisible

Even older, experienced attorneys aren’t immune. Bass of the ABA calls it “success fatigue.”

“It’s always harder for women to achieve the same level of success,” Bass said, “and at some point after 20 years you just say ‘Im done, I’m not doing this anymore.'”

She said so much experience walking out the door comes at a tremendous loss for the firms and clients. “This is a time of maximum expertise, maximum experience. You should be enjoying the fruits of 20 years of your labor.”

Deutsch said she recently spoke to a woman in her 50s who was a partner at a major law firm.

“She said the older she got, the more invisible she got at the firm. She became more expendable. This is something I hear from my women clients: the older they get, the more senior they get, they’re sort of lost in some ways.”

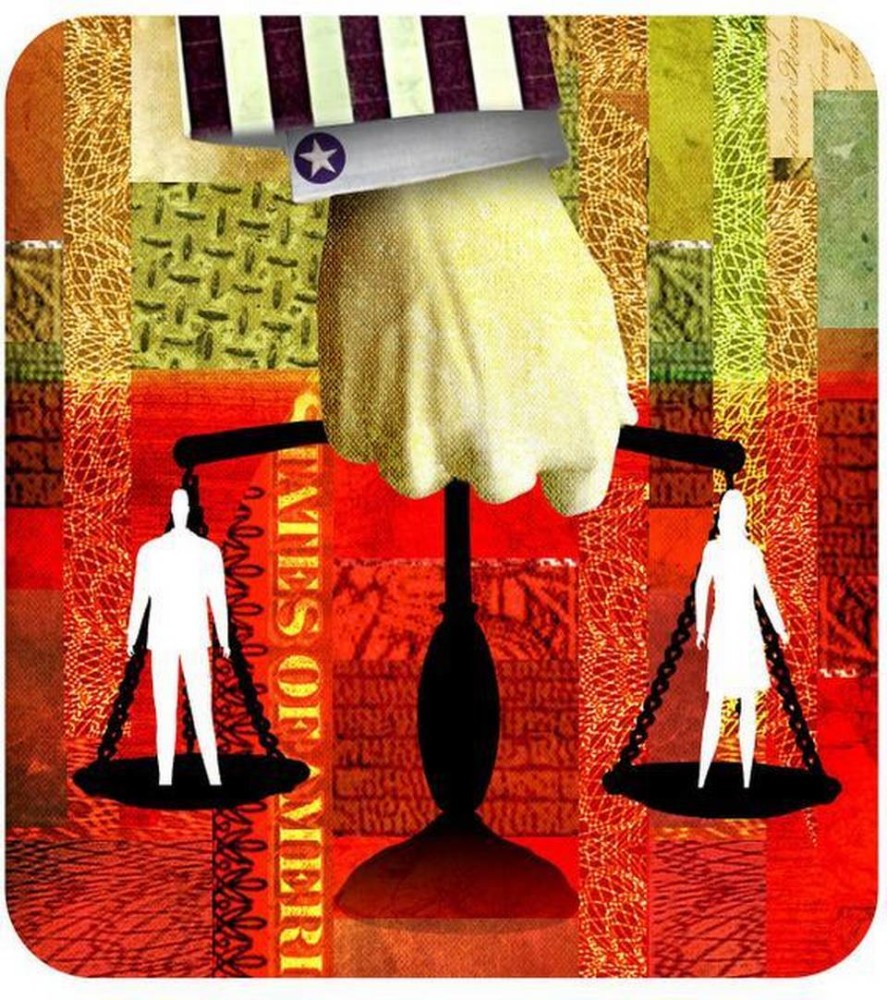

It’s why Sharon Rowen — an Atlanta attorney whose latest documentary, “Balancing the Scales,” charts the challenges that successful female lawyers have had to overcome — is naming her next film “An Invisible Truth.”

“You can’t get anywhere in terms of women being promoted to where they should be, or qualified to be, if they become invisible at a certain point,” Rowen said in an interview. “Women are not looked at as leaders. They are looked at as helpers, mothers, workers, people who get the work done.”

Why does diversity matter? Rowen offered at least one reason: Money.

“There’s a body of research that talks about economically why we should care: companies are more profitable when there is diverse leadership,” she said

Plus: “Women are half of the population,” Rowen said, “why would you want them to feel second class?”