By Shan Li

Los Angeles Times.

LOS ANGELES

The alterations underway at American Apparel Inc. are evident in its advertising. Gone are the half-naked young women splayed on billboards and print ads. These days, the models tend to be fully dressed in the company’s hip basics.

The salacious images were part of the freewheeling style of founder Dov Charney. His tenure was also marked by loose corporate operations, financial losses and sexual harassment allegations that sparked a board revolt and Charney’s ouster last year.

American Apparel ads will still have an edge, some incorporating social issues such as gay rights, bullying or women’s equality, but they won’t be “sexual for sexual’s sake,” new Chief Executive Paula Schneider said in an interview with the Los Angeles Times.

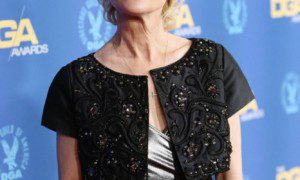

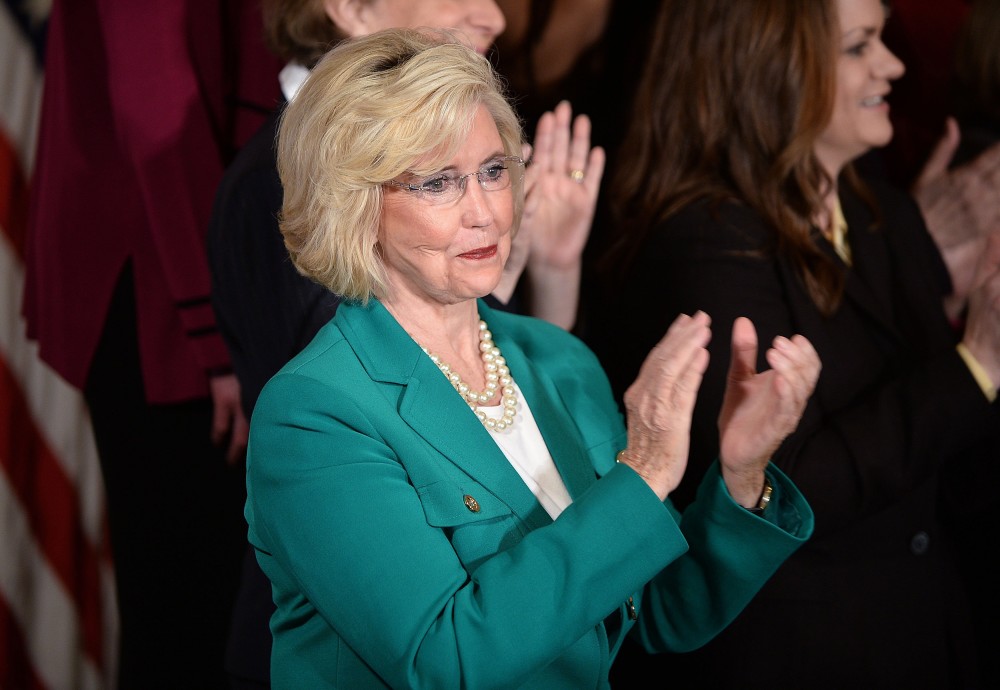

Schneider, a longtime clothing executive who took over in January, hopes to transform more than the advertising at the Los Angeles clothing firm, which employs nearly 10,000 people and operates almost 250 stores. In nearly five years, American Apparel has lost $310 million. Its debt totals more than $200 million.

Beyond toning down the oversexed image, Schneider aims to install a more grown-up structure and culture to replace Charney’s eccentric micromanagement. Schneider is focused on the boring-but-important details of hiring, and empowering, experienced managers and drawing up evaluation protocols and organizational charts.

Schneider, 56, has spent decades at clothing retailers and manufacturers. She has held senior executive positions at retailers such as BCBG Max Azria and Laundry by Shelli Segal. At BCBG Max Azria, she helped steer the company to profitability, and at Warnaco Group, she aided in a corporate restructuring.

Since arriving at American Apparel in January, Schneider has sought to order the corporate chaos without sacrificing the brand’s soul.

“It’s getting everybody in their lane and understanding we have a common goal,” she said. “There is tremendous energy here; there is tremendous love for the brand; there are tremendous ideas. It’s just a matter of saying: What do we do with them? How do we harness it? What do we do to move it down the road?”

Schneider’s management style is sharply different from Charney’s, who often inserted himself into the smallest details. Charney handpicked models for ads, selected fabrics and even cleaned retail stockrooms.

American Apparel’s new chairwoman, Colleen Brown, said Schneider was tapped in part for her ability to instill organization.

Under Charney, the company didn’t have many of the formal controls common at public companies, she said. There was no standard method for performance reviews, for example, and department heads had no regular meetings.

“The really easy things are hard at American Apparel,” Brown said. “Just basic systems and processes that allow you to make decisions easily.”

Schneider has a track record of boosting ailing companies, Brown said.

“She has driven several turnarounds in her career, and that was an important thing to consider when we were looking for a CEO,” she said. “The company has not made money for a while, so we needed someone who could get a strategic plan and put it into place.”

Schneider still has until April 5 before she is required to present her operational plan to the board, according to a security filing that detailed her contract. Barely two months into the job, Schneider has already started making changes.

One example: She has bulked up the planning department, which orders raw materials to keep the factories humming. With better forecasting, the company can save money by buying more yarn overseas or can ship supplies and products by ground instead of air, Schneider said.

Another focus is design and marketing.

Last month, the company fired its two longtime creative directors, Iris Alonzo and Marsha Brady, both Charney allies. Schneider said the firings weren’t a result of poor performance but merely a shift in creative direction.

“We have a lot of really talented people, but young,” Schneider said, adding that some lack the formal training and education typically found at a major manufacturer.

She has already made product changes too.

Fewer styles will be offered in the fall season, Schneider said. Instead the company will concentrate on offering styles in more color variations, a move to avoid a problem that analysts say plagued American Apparel: offering too many products, many that didn’t sell well.

E-commerce will also get a close look. Among the new hires is American Apparel’s first chief digital officer, who will be in charge of improving the online shopping experience and boosting digital sales, Schneider said.

The company currently gets only 15 percent of its sales from e-commerce. By comparison, teen retailer Abercrombie & Fitch’s online side accounted for 20.2 percent of net sales in the first three quarters of its 2014 fiscal year.

“When we look at it compared to our peers, there is a lot more room to grow,” Schneider said.

Each department was also tasked with coming up with its own budget for the year, in sharp contrast to the “top down” approach of the past, she said.

Schneider said she has no choice but to push decision-making power down through the ranks.

“When you have a founder that knows everything about the business … you come in and you are not that person,” she said. “You have to have some people in each area that are going to be the leaders in order to function.”

Ilse Metchek, president of the California Fashion Association, said Schneider may struggle to win over employees and institute a more traditional corporate culture.

“Everyone there was hired by Dov, and everyone is still probably loyal to Dov,” she said.

One core feature of American Apparel, its made-in-USA model, will remain firmly in place.

Walking through the factory filled with the steady hum of sewing machines, Schneider marveled at the scale of the operations, in an 800,000-square-foot salmon-colored building in downtown Los Angeles.

Echoing Charney, Schneider bragged about the company’s ability to quickly whip up new garments and get them to its shops.

The company can get a new product into stores on a Thursday and know if it’s a strong seller by Monday, she said. Then the local factory can immediately respond.

“We can make that same version, we can make it in colors, we can make it longer, shorter, long sleeved, short sleeved, and we can put it into our stores in a week,” she said.

Schneider compared American Apparel’s main factory, which employs more than 3,000 cutters, sewers and other workers, to “a city.”

The facility also includes an on-site medical clinic and masseuses that offer free massages. The operation is so vast that Schneider said she prefers to think of slices of the company individually.

“Otherwise,” she quipped, “I’d be up all night.”