By Katy Murphy

The Oakland Tribune.

SAN FRANCISCO

The aspiring app developers and entrepreneurs attending the new Make School in San Francisco don’t take out loans to cover tuition.

There is no tuition — at least up front.

Students pay 25 percent of their salaries back to the school in their first two years in the workforce, as well as internship earnings. If they don’t find a job in the tech field — or if their startup fizzles — the school gets nothing.

The two-year Make School, a highly selective startup preparing students to enter the lucrative tech sector, is hardly a typical American college. But its model, billed as “debt-free education,” reflects the collective national angst over student loans and college affordability.

It’s been decades since California abandoned its famed tuition-free promise, but as tuition nationwide spirals upward, stressing middle-income and poor families alike, “debt-free college” has suddenly gone from nostalgic fantasy to political sound bite.

“It’s moving as quickly as any recent issue that I can think of,” said Reid Setzer, policy and legislative affairs analyst for Young Invincibles, a research and advocacy group for millennials based in Washington, D.C.

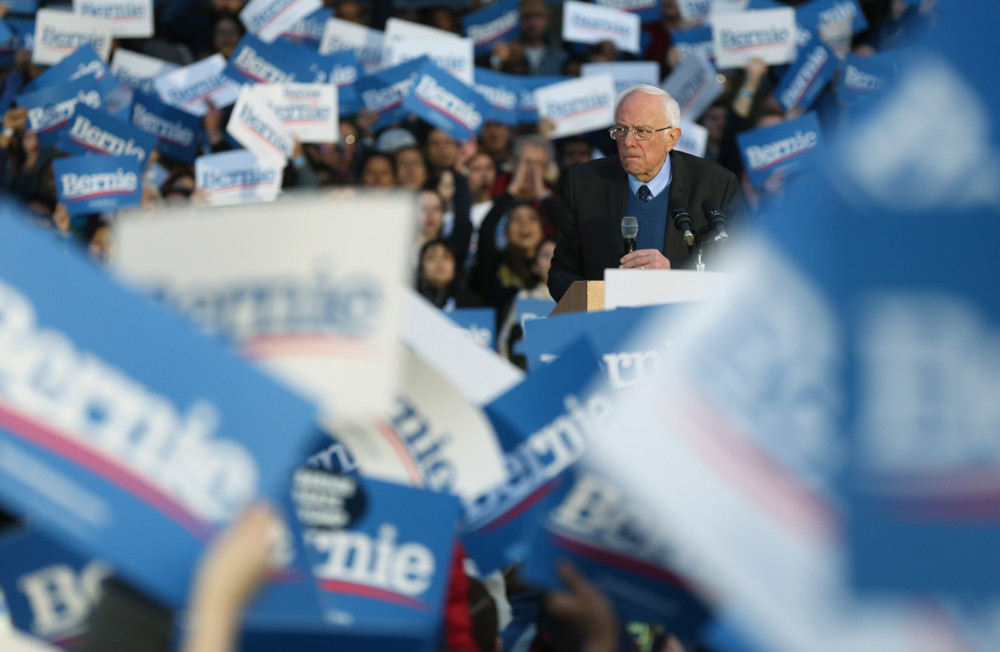

The issue has crystallized as a central one in the Democratic presidential race, with Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders and Martin O’Malley all calling for the federal government to spend hundreds of billions of dollars over the next decade to make college affordable.

In January, President Barack Obama used his State of the Union address to unveil a plan for free community college, prompting lawmakers in nearly a dozen states to introduce legislation to that effect. In April, a group of congressional Democrats, including influential Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, went further. They introduced twin resolutions to make all public universities — not just two-year colleges — debt-free.

By August, Clinton had released her own higher-education affordability plan, complete with a $350 billion price tag.

Democrats embraced “debt-free college” after getting trounced in 2014 midterm elections and seeing how well the issue resonated with voters, political analysts say.

A poll by the Progressive Change Institute in Washington, D.C., found that nearly half of Democratic voters who skipped that election “definitely” would have gone to the polls if college affordability was at stake. Out of dozens of progressive causes that might have motivated those voters, “debt-free college at all public universities” rose to the top of the list, the poll found.

The unique deal at the Make School appeals to students like Leslie Kim, 27, of San Francisco, who said she would not have gone back to school if she had to borrow to do it. Taking out loans felt like too much of a risk.

“I didn’t want to incur any debt,” she said.

And it’s no wonder: The debt burden for the average bachelor’s degree recipient rose at more than twice the pace of inflation from 2004 to 2014 — to nearly $29,000, according to a new report from the Oakland-based Institute for College Access & Success.

Under Clinton’s proposal, families would pay what they could afford for tuition, but wouldn’t have to take out a loan to cover tuition and fees. Sanders’ plan would “eliminate undergraduate tuition” at public universities, with the federal government picking up two-thirds of the tab. O’Malley’s proposal would expand Pell Grants and call on states to freeze tuition. All the Democratic candidates have also proposed allowing borrowers to refinance their loans at lower interest rates.

The GOP candidates have been noticeably silent on the subject.

“I think Republicans will get to this issue, but they’re not there yet,” said Terry Hartle, senior vice president of the American Council on Education, which represents college presidents at some 1,700 institutions nationwide.

Ashu Desai, the 23-year-old cofounder of Make School, said widespread concerns about student debt and abuses in the for-profit college sector influenced his decision not to charge tuition up front. Instead, the school charges a percentage of graduates’ wages — or, alternatively, an investment in their startup — instead of a flat fee.

“If you have $100,000, $200,000 in loans,” he said, “you’re not going to be an entrepreneur.”

But one expert took issue with Make School’s claim that it offers a “debt-free education,” given that the average graduate is expected to eventually pay a total of $80,000.

“That’s exactly what a loan is,” said Sandy Baum, who has coauthored the College Board’s annual report on college-pricing trends and who has advised Hillary Clinton’s campaign. “I think that anything that disguises debt as something else is worrisome.”

Several Make School students interviewed for this story said they think the delayed payment ensures the school will give them the kind of training and mentoring they need to succeed. The first class of 32 students, most in their late teens and early 20s, will spend their two years attending lectures, interning at local companies and working on their own projects.

“I think it’s a really good model,” said Ryan Kyungheui Kim, 23, who lived in Korea, India, Idaho and Los Angeles before moving to San Francisco. “The school needs to make sure the students are doing fine so they get a good job.”

Debt-free college means different things to different people, Hartle said, but politically it has become a metaphor for college affordability. As time goes by, he added, policymakers will need to be more specific: Which students will benefit from the plans? Will private institutions be included? What strings will be attached to the federal money? And where will all the money come from?

“Talking about paying for something that could be this expensive is a real buzz kill,” Hartle said. “The cost of these programs could be frightfully expensive.”