Andrew A. Smith

Tribune News Service

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Andrew Smith Shares his top pics for powerful graphic novels which feature amazing, strong, creative women.

TNS

Once again, gals have taken over the better graphic novels I have for review. Let’s meet them:

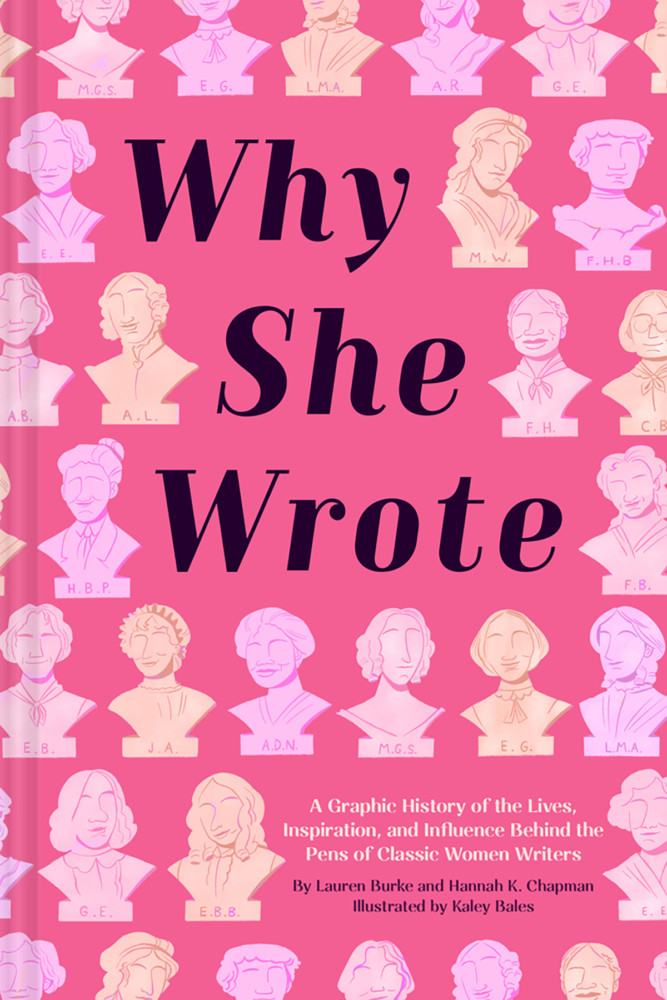

‘Why She Wrote: The Graphic History of Classic Women Writers’

Written by Lauren Burke and Hannah Chapman, art by Kaley Bales

Chronicle Books, $19.95

“Why She Wrote” is that rare book I can recommend without qualification. Well, unless you don’t like literature or women, in which case, why are you my friend?

“Why She Wrote” has taught me a lot of history about famous female writers I was surprised to discover I didn’t know. That is to say, in school I read books like “Jane Eyre” and “Wuthering Heights,” but I didn’t know much about the authors, or the environment in which the books were written (which is often necessary to understand them fully). I mean, I was probably in high school before I realized there was more than one Brontë!

That’s an important void in my education, one this book actively corrects.

And what fun it is! I had no idea how much of “Frankenstein” was a metaphor for Mary Shelley’s life and outlook. Or why Charlotte Brontë was so interested in women locked in attics. And here’s a kicker: Since “Jane Eyre” mentioned Ann Radcliff and her “The Mysteries of Udolpho,” until yesterday o’clock I thought Radcliff was a fictional character, like everyone else in the novel.

Needless to say, this misapprehension has been corrected, and my thirst to read me some Radcliff has been stoked. Did you know she virtually invented the Gothic genre? Well, if you didn’t, now you do.

For the record, the book profiles Louisa May Alcott, Jane Austen, Anne Brontë (aka Acton Bell), Charlotte Brontë, Emily Brontë, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Frances Hodgson Burnett, Frances Burney, Edith Maude Eaton (aka Sui Sin Far), Mary Anne Evans (aka George Eliot), Elizabeth Gaskell, Frances E. W. Harper, Anne Lister, Alice Dunbar Nelson, Beatrix Potter, Ann Radcliffe, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft.

The art is a bit on the cartoony side, but attractive and flexible enough to cover the different eras, fashions and concepts involved. Recommended.

‘The Curie Society TPB’

Written by Janet Harvey, illustrated by Sonia Liao and Johanna Taylor

MIT Press, $18.95

When teen science prodigies Maya, Simone and Taj become roommates at (the fictional) Edmonds University, they are inducted into the (also fictional) all-female, all-scientist Curie Society. The secret organization was founded in 1903, we are told, so “brilliant women could pursue the furthest reaches of their intellect.”

The three have to pool their skills to join the society, which is just phase one. Phase two is the “save the world from evil scientists” part, which is more or less standard teen-detective action/adventure.

But with STEM! Which is what elevates this book above genre formula.

Honestly, the plot is pretty familiar, as is the After-School Special lesson that our fractious heroines have to learn to work together to achieve their aims. The girls are all multiculti, and one of them isn’t on the gender binary.

That’s almost standard procedure these days.

What sets “Curie Society” apart from all its “Encyclopedia Brown”/”Hardy Boys” young-adult brethren is A) all the good guys are gals, B) the girls are well developed as individual characters and C) real-world science is involved at every turn. Like “The Martian” — which the catalog copy actually references as an inspiration — our fledgling heroes have to employ real science. The book also includes biographical data on the scientists mentioned and the book’s science advisers, as well as a glossary of science terminology.

If I had a daughter in middle school, this book would be in her library. There aren’t enough books to inspire girls about math, science and technology (although that’s changing), so I welcome this one.

‘A Sister’

By Bastien Vivès

Ablaze, $24.99

Everyone remembers their first kiss, right? And all the awkward stuff that comes with that — fumblings in the backseat, nervous moments on the front porch, and like that?

Well, that’s the usual American version of coming of age, anyway. In “A Sister,” we get a French version.

But regardless of nationality, or gender, or era, those first, stumbling steps into adulthood are both wonderful and terrifying for everyone. Those feelings are seared in our memories, even if the events themselves get a little foggy over time. Nobody ever gets so sophisticated as to forget the days when they weren’t.

And it is those feelings that “A Sister” nails.

The story is this: Teenage (13-ish) Antoine is on vacation with his parents and younger brother at the sea, somewhere in Europe. Antoine and his brother spend most of their time drawing, an obsessive hobby that afflicted my younger self as well.

But then Hélène (16-ish) and her mother come to stay with Antoine’s family. Which changes everything.

Hélène is a full-blown teenager, full of impatience and angst and defiance. Antoine is a bit more subdued. These teens are at either end of that short, awkward, wonderful time, and it is there they find each other.

But Hélène, being older, is the one who takes charge. She introduces Antoine to drinking. And dancing. And some other things that make this a “Mature Readers” book.

Now, don’t get me wrong. This is a coming-of-age story, not pornography. There’s no romping in the sheets, nor a full Monty. But these are teens who are neither children nor adults, with a foot in each camp, and there is the physical experimentation that goes along with that. I just thought I should toss that warning out there.

But it’s not the focus. It’s part of the whole story, the story of Antoine and Hélène, two kids who seem to genuinely like each other, but for whom this is but a bittersweet pause on the precipice of growing up. And they both know it. It is, you’ll forgive me, painfully poignant.

The art is a sort of sketchy, delicate wash that increases the feeling of universality by eliminating most identifying detail. And I was puzzled at first by Vivès’ habit of drawing faces without eyes. “Maybe he just doesn’t like drawing them,” I thought. But then it dawned on me that removing the eyes removes their identity, making it easier for the readers to cast themselves as one of the characters.

buy viagra black generic buy viagra black online no prescription

And I surely did. I’m on the far end of the “Mature Reader” scale, but again, nobody forgets that time, those frozen moments of in-between, and I am no different. I can remember 13 better than 30, because the former was so raw.

Deft, intelligent and sensitive, “A Sister” is both ethereal and earthy. That makes it natural for a movie, and sure enough, it’s being adapted to film by Charlotte Le Bon (“Yves Saint Laurent,” “The Walk”).

But don’t wait for that when you can read the book right away. Even if you’re not French.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC