By Jennifer Dixon

Detroit Free Press

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) Researchers examine the effect violence and poverty have on a students’ ability to learn and perform in the classroom. The studies also take a look at the long-term consequences for children.

Detroit Free Press

This is one in a series of stories on efforts to improve children’s lives. The Free Press spent a year talking to children across Detroit about how they live and what issues they see as most important. Safe neighborhoods, schools, job opportunities, teen pregnancy and help for young parents were among key issues raised.

Based on these conversations, as well as community meetings and a poll, the Free Press looked at efforts both locally and around the country. This project was done with a $75,000 grant from the Solutions Journalism Network, a New York-based nonprofit that partners with newsrooms around the country to do projects that focus on solutions to social issues.

Researchers call it “toxic stress.”

It’s the response some children have to prolonged adversity — whether it’s the burden of living in extreme poverty or being exposed to violence, physical or emotional abuse, or chronic neglect.

Children who experience excessive stress face immediate and lifelong problems with learning, behavior, and physical and mental health.

According to researchers:

* Prolonged exposure to fear can impair early learning and affect performance in school, at work and in the community. One researcher found that children who took reading or vocabulary tests shortly after being exposed to a murder in their neighborhood performed dramatically lower — as though they’d lost several years of academic progress.

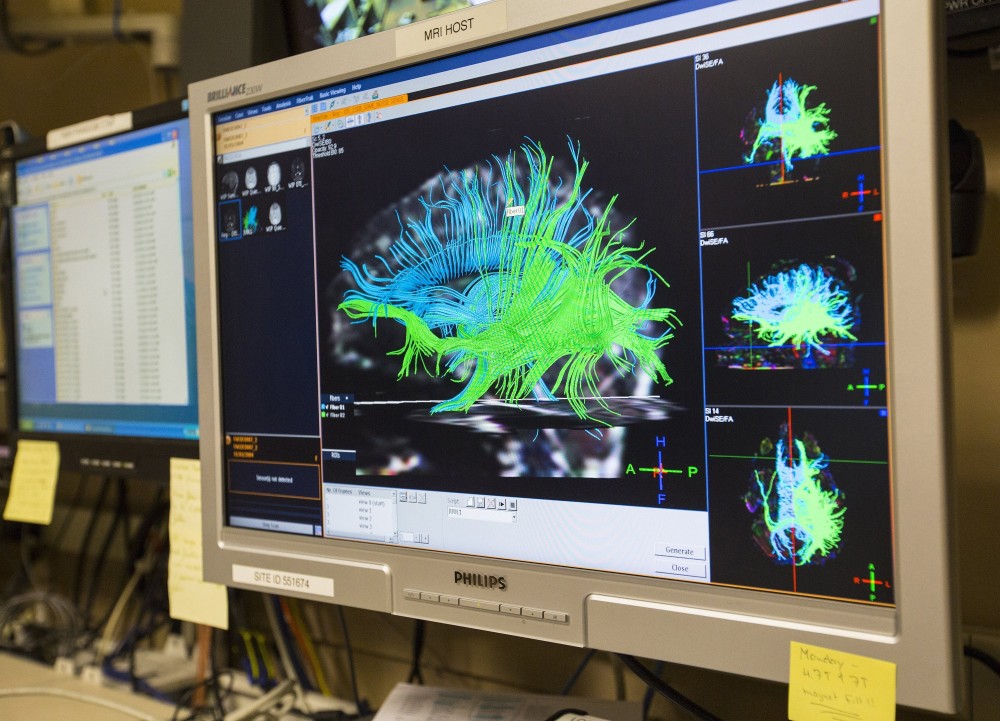

* The brain’s circuitry can be disrupted by chronic stress.

* The long-term impact of toxic stress can include diabetes, heart disease, depression, substance abuse and a shortened life span.

* Removing a child from a dangerous environment will not undo the serious consequences or reverse the impact on the brain.

* Fears are not forgotten over time and must be actively unlearned.

Researchers say the findings underscore the importance of prevention and early intervention.

“Society reaps what it sows in the way it treats its children,” said Dr. Martin Teicher, a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and a leading expert on how child abuse and neglect, specifically, can cause physical changes to the brain.

“You’ll have generation after generation of problems if children grow up in a situation with a lot of adversity and strife.

It’s really important that we nurture our children and provide a safe and supportive environment so they can really reach their potential.”

Teicher, whose lab and research are based out of the Harvard-affiliated McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass., said some regions of the brain are sensitive to maltreatment early in life, others during preteen and teenage years.

Dr. Jacek Debiec, a neuroscientist and psychiatrist at the University of Michigan, said he has treated children and teenagers who experienced childhood trauma.

“We know that long-term stress may alter the brain, even alter (it) irreversibly,” said Debiec, who researches brain development in animals and the way newborns form bonds with their parents.

For example, the area of the brain called the amygdala, which is important for processing danger, “tends to be enlarged and hyperactive after an exposure to a prolonged stress,” he said. And the hippocampus, the brain structure that is important for learning and memory, shrinks when a person is subject to severe stress, “which means that the child …may have problems with learning, with staying focused, and with many tasks that require learning and memory, including unlearning previous traumatic experiences.”

The main goal of treatment is “to restore the feeling of safety,” a process that may be long and demanding because it is already complicated by the trauma-induced alterations of critical brain networks, Debiec said.

While most mental health illnesses have a strong genetic component, he said, the “social environment does matter.”

Research also shows that while some experiences might be one-time events and others may persist over time, “all of them have the potential to affect how children learn, solve problems, relate to others and contribute to their community,” according to a 2011 paper written by Nathan Fox, a professor at the University of Maryland who has done research on human developmental neuroscience, and Dr. Jack Shonkoff, a professor of child health and development and pediatrics at Harvard University.

According to the university’s Center on the Developing Child, which Shonkoff directs, the mental and physiological effects of stress are buffered if a child grows up in an environment of supportive relationships. But if the stress response is extreme and long-lasting and buffering relationships are unavailable, a variety of biological systems may be primed for breakdown in adulthood.

David Marshall, a neuropsychologist and assistant professor in the University of Michigan’s Psychiatry Department, is involved in the country’s largest long-term research study of bipolar disease, one of the mental health illnesses linked to childhood trauma.

His research has found that participants who experience childhood trauma score more poorly on impulse-control tests than those who didn’t suffer childhood trauma. He said that’s important because impulse control impacts all kinds of decision-making: from acting out as a child to abusing alcohol or drugs as an adult.

Marshall said the findings underscore the need to teach adults and children coping strategies as early as possible, even though not everyone exposed to trauma will develop mental health issues.

Another area that researchers are delving into: how some children exposed to trauma develop resilience, or the ability to overcome serious hardship, and others do not.

According to the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard, the single most common factor for children who develop resilience is having at least one stable and committed relationship with a supportive parent, caregiver or another adult. Resilience can be strengthened at any age.

Understanding resilience is important, the center said, because the science can be used to improve programs and policies to help more children reach their full potential.

Living in extreme poverty can cause chronic stress because it is often accompanied by many stressful factors: violent communities, violent relationships, noise and pollution, lack of food, and chaotic environments and schedules. Whether it becomes toxic stress largely depends on the adults in the child’s life and whether they have the ability to buffer the child from stress.

Toxic stress also has implications for learning, according to Patrick Sharkey, a professor of sociology at New York University who got his doctorate in sociology and social policy from Harvard.

In launching his research on children and violence, Sharkey had one specific question: Does the shock of a murder affect a child’s academic achievement, attention span and impulse control?

The answer: Yes. And the impact is significant.

Sharkey began his research by reanalyzing assessments of the cognitive skills of children in Chicago gathered by other researchers, and matching those assessments to information on homicides occurring in the children’s neighborhoods. The closer the homicide to the day of the assessment — and the closer to the child’s home — the worse the results.

When he compared two children in the same neighborhood, the child tested within days of a homicide performed much worse on reading and vocabulary tests than a child tested before a murder.

“The closer the homicide, in time and space to the child, the bigger the impact,” Sharkey said in a phone interview from Nepal, where he is on sabbatical. The impact of a murder close to the home within four days of the assessment was “enormous” — as though the child “missed two or three years of school. It may not be surprising that local violence affects children, but what was really surprising was the magnitude of the impact. It was that strong.”

While his research doesn’t tell anything about the permanent impact on cognitive development, he said children in the most violent neighborhoods may spend as much as one-fourth of the year functioning at a lower level at home and in school.

“If the effects of local violence compromise students’ ability to learn, to maintain attention and to perform well in the classroom, the long-term consequences for children’s educational trajectories may be severe,”