By Cathleen Decker

Los Angeles Times.

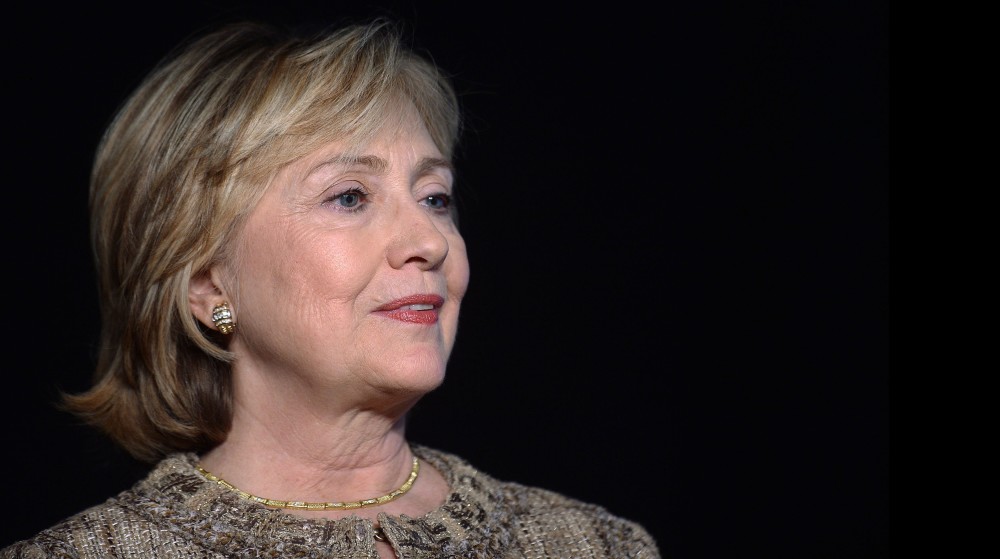

Much of Hillary Rodham Clinton’s 2008 presidential campaign was a disaster. The candidate was often stilted and imperial, finding her voice only when there was no chance she would win.

Jill Abramson’s tenure as executive editor at the New York Times has been marked by reported disputes with those around her, culminating in Wednesday’s surprise announcement of her firing by publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr.

So maybe both women, known publicly as much for their flaws as their attributes, deserved their fates. But their falls from grace nonetheless played on gender turf that is likely to be trod all over again in 2016 if Clinton opts for a second try for the presidency.

There have been more than a few searing where-were-you moments in recent years which drew wildly different responses, depending on gender.

In 1991, law professor Anita Hill accused Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas of unwanted sexual comments and found the all-male Senate Judiciary Committee unwilling to hear out the women who supported her accusations. The committee members, led by now-Vice President Joe Biden, seemed to be bollixed up by fear of looking like they were participants in what Thomas called a “high-tech lynching.”

In 2008, Clinton found her campaign suffused with sexist insults: men in the audience chanting “Iron my shirts,” Arizona Sen. John McCain laughing after being asked how to “beat the [rhymes with witch],” cable pundits who compared Clinton to hectoring mothers and the deranged bunny-boiling character in the film “Fatal Attraction.”

Then there was the Hillary Nutcracker, a representation of Clinton with serrated blades lining her inner thighs.

In an odd replay of the Clarence Thomas hearings, the co-creator of the nutcracker explained in a 2008 interview that he “thought it was funny” but could not imagine something similar mocking Clinton’s rival, Barack Obama, or the GOP nominee, McCain.

“One is African American, and there’s where you run into problems,” said Gibson Carothers, who at the time said he’d sold 200,000 nutcrackers. It was more acceptable, he suggested, to mock the woman.

And then, this week, the Abramson affair. In the beginning, it seemed like a standard-issue power struggle that the first female editor of the nation’s most legendary newspaper had lost. Maybe that is what it was, but other details surfaced to complicate the picture.

Abramson had fought to extract the same pay as her male predecessor, and discovered that when she was managing editor, a male deputy had made more money, according to New Yorker media writer Ken Auletta.

“She had a lawyer make polite inquiries about the pay and pension disparities, which set them off,” he quoted an anonymous Abramson loyalist as saying.

NPR media reporter David Folkenflik confirmed that account and added that Sulzberger was uncomfortable with the publicity Abramson received (much of it due to her history-making role).

“Sulzberger didn’t love that profile,” Folkenflik tweeted, referring to the public notice Abramson attracted.

Sulzberger told his staff Thursday that Abramson’s pay was “comparable to that of earlier executive editors” and that discussion of it “played no part whatsoever” in his decision to remove her.

“The reason — the only reason — for that decision was concerns I had about some aspects of Jill’s management of our newsroom, which I had previously made clear to her, both face-to-face and in my annual assessment,” he said.

No matter which side seemed persuasive, the murky aftermath spoke to a persistent issue for women in the workplace: how to navigate between roiling the waters enough to be noticed and upsetting your own canoe.

One of the perks of equality, of course, is that you can get canned from far better jobs than in the past. And you can get beaten by people better at the game.

Obama’s strategy and personality were a far better match to the mood of 2008 than Clinton’s, and his campaign executed far better, to boot. (Abramson’s replacement, former Los Angeles Times editor Dean Baquet, is hugely popular in the industry and now makes history of his own as the first African American to lead the New York Times.)

Clinton, in her 2008 race, played down the history her victory would have represented, making a strategic decision to instead emphasize experience and toughness, occasionally reinforcing the image by belting down beer and whiskey in a local bar.

As she approaches a decision in the next several months on whether to run again in 2016, she has adopted a dramatically different approach, speaking repeatedly about what she has called a “double standard” facing women seeking important roles.

It has something of an in-your-face feel to it, suggesting Clinton figures either gender turf has changed or she has more to gain from trying harder to engage women than not.

Whichever it is, and whether she is right, may determine whether she does, in fact, shatter the ultimate glass ceiling.