By Justin Chang

Los Angeles Times

WWR Article Summary (tl;dr) “The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley,” is a new HBO documentary on Elizabeth Holmes, the self-styled biotech visionary who founded a company called “Theranos.” Its top-secret weapon was a compact machine called the Edison, which could purportedly run more than 200 individual tests from just a few drops of blood, obtained with just a prick of the finger.

Los Angeles Times

As a quick glance at recent headlines will remind you, a staggering college admissions scandal, a wave of indictments in the cases of Paul Manafort and Jussie Smollett, we are living in deeply fraudulent times.

But if there are few people or institutions worthy of our trust anymore, perhaps we can still trust that, eventually, Alex Gibney will get around to making sense of it all.

Over the course of his unflagging, indispensable career he has churned out documentaries on Scientology and Enron, Lance Armstrong and Casino Jack, individual case studies in a rich and fascinating investigation of the American hustler at work.

Gibney approaches his subjects with the air of an appalled moralist and, increasingly, a grudging connoisseur.

His clean, straightforward style, which usually combines smart talking heads, slick graphics and reams of meticulous data, is clearly galvanized by these charismatic individuals, who are pathological in their dishonesty and riveting in their chutzpah. And he is equally fascinated by the reactions, ranging from unquestioning belief to conflicted loyalty, that they foster among their followers and associates, who in many cases shielded them, at least for a while, from public discovery and censure.

“The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley,” Gibney’s latest exercise in coolly measured outrage, is an engrossing companion piece to his other works in this vein.

The subject of this HBO documentary is Elizabeth Holmes, the self-styled biotech visionary who dropped out of Stanford at age 19 and founded a company called Theranos, which promised to bring about a revolution in preventive medicine and personal health care.

Its top-secret weapon was a compact machine called the Edison, which could purportedly run more than 200 individual tests from just a few drops of blood, obtained with just a prick of the finger.

Holmes’ vision of a brave new world, one in which anyone could stop by Walgreens and obtain a comprehensive, potentially life-saving snapshot of their health, proved tantalizing enough to raise more than $400 million and earned her a reputation as possibly the greatest inventor since, well, Thomas Edison.

Her investors included Betsy DeVos, Rupert Murdoch and the Waltons; Henry Kissinger, George Shultz and James Mattis sat on her board of directors.

But that was all before the Wall Street Journal’s John Carreyrou and other investigative journalists exposed glaring faults in the Edison’s design and sent the company’s $10-billion valuation spiraling down to nothing.

Theranos dissolved in 2018, and Holmes and former company president Sunny Balwani were charged with conspiracy and fraud.

Full disclosure: As the son of a retired medical technologist who spent more than 30 years testing blood the traditional way, I approached “The Inventor” with great fascination and more than a little schadenfreude.

The movie, for its part, seems both magnetized and repelled by its subject, a reaction that it will likely share with its audience.

Gibney is perhaps overly fond of deploying intense, lingering close-ups of Holmes’ face and peering deep into her unnerving blue eyes (“She didn’t blink,” a former employee recalls). If the eyes are the windows to the soul, “The Inventor” just keeps looking and looking, as though uncertain whether or not its subject has one.

The movie is thus not entirely immune to the very spell that it seeks to diagnose, namely, the captivating image of Holmes as a strikingly focused and self-assured young woman thriving within the male-dominated ranks of tech innovation.

But it submits to that spell, ultimately, in order to shatter it from within. Holmes unsurprisingly opted not to participate in the documentary, but her presence is inescapable throughout “The Inventor,” due to not only recordings of her many public appearances but also hours of promotional footage that fell into Gibney’s hands.

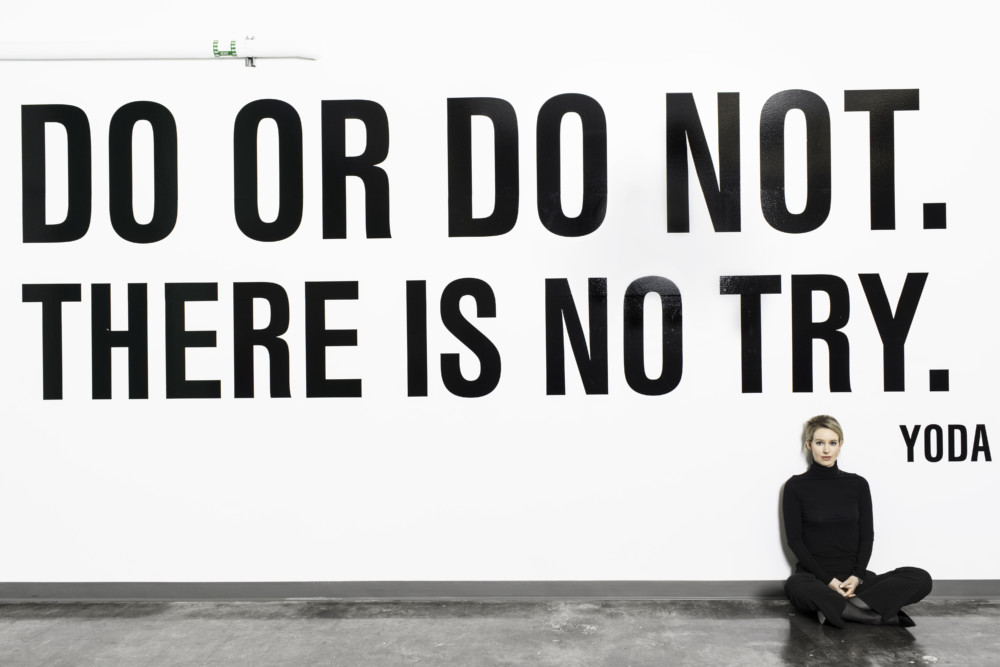

When we see Holmes walking around the company’s gleaming Palo Alto offices, always wearing black turtlenecks that invited open comparison to one of her idols, Steve Jobs, or revving up her staff with assurances about the importance of the work they’re doing, we are effectively seeing Theranos as it sought to present itself to the world.

And as Gibney knows, damning his subjects is always less efficient, and less effective, than letting them do it themselves. (He does sneak in a dig at fellow documentarian Errol Morris, whom we see being brought in to film Holmes, identifying himself as “a fan.”)

And so “The Inventor” becomes less an expose of white-collar crime than a study in the power of self-delusion and corporate megalomania.

Gibney’s methods are simple but often brutally effective. He juxtaposes the self-flattering corporate imagery with his own sobering interviews with former Theranos employees, who describe a culture of intense secrecy and paranoia, grotesque technical and ethical malfeasance, unreliable test results and dangerously malfunctioning equipment.

There may be no more nightmarish movie image this year than the graphic mock-up of the inside of an Edison prototype, a Pandora’s box of infected needles, broken vials and blood-spattered surfaces.

The name of the machine naturally spurs some discussion of Thomas Edison himself, who, we’re reminded, also blurred the roles of innovator and showman, genius and huckster. But Holmes successfully convinced a lot of people that she was all genius. She learned to ingratiate herself early on with people of wealth and influence, and to ignore naysayers like Dr. Phyllis Gardner, the Stanford medical professor who warned Holmes that what she was proposing, a device that could perform more than 200 extremely precise medical/technical functions in a container small enough to fit on your kitchen counter, was impossible.

It’s a pleasure to hear from voices of sanity, like former Fortune editor Roger Parloff, who speaks with palpable chagrin over having been deceived by Holmes and Theranos.

Those voices are among the obvious dividends of “The Inventor,” which otherwise offers few fresh insights or revelations beyond what has already been reported. (That includes Carreyrou’s 2018 book, “Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup.”) Like a lot of Gibney documentaries, it compresses a juicy, complicated story into a smooth, coherent retelling that occasionally glances at that story’s deeper implications.

You might leave “The Inventor” thinking about the dangers of trying to revolutionize something as universal (but also as specific) as human health, or wondering why we are so easily enthralled by the seductive, often specious language of technological disruption.

You might also be tempted to read up on Holmes and her continued insistence on seeing herself as not the villain but the victim in her own story, which suggests she might in fact be the biggest sucker of all.

___

‘THE INVENTOR: OUT FOR BLOOD IN SILICON VALLEY’

Not rated

Running time: 1 hour, 58 minutes