By Robert Lloyd

Los Angeles Times.

There is a lot of talk going around these days, about nothing in particular and about everything in particular.

In the nexus of entertainment and information that includes what we traditionally have thought of as television and radio and that which we call the Internet, a collection of mediums that have begun to blend together as they reach us increasingly across the same platforms, one modality rules over all: talk. The talk show, the podcast, the story hour.

It’s customary to speak of the New Golden Age of Television as a function of quality drama. But network TV begins and ends its day with talk, from “Today” to “Tonight,” “Late Night” and “Last Call,” where questions are being asked and answered. We wake up with talk, make eggs with talk, drive to work with talk; we crawl into bed with talk. In the middle of the day, there is a show called “The Talk,” which, like its inspiration, “The View,” transforms the coffee klatch into a television series. Cable news is all talk, all the time.

It’s not a new story; in fact, if we want to rope in Homer and the people whose fairy tales the Grimm Brothers collected, it’s an old one. Debates and speeches were popular entertainment in pre-electronic America. (The famous Lincoln-Douglas debates lasted three hours each, precisely as long as our own prime time.)

There is nothing in television more institutional than a talk show, “The Tonight Show” is nearly 61, “Today” 63. Terry Gross has been hosting the public radio interview show “Fresh Air” for 40 years; “All Things Considered,” a habit for millions, is 44. Even the word “podcast” has been in the Oxford English Dictionary for a decade.

So easy to just … talk

What is new is the proliferation of platforms and of possibilities, the widening of the market. In broadcasting, talk is the easiest thing to do, requiring a minimum of technical know-how, little preparation and almost no overhead; “podcasting kits,” with “all you need to get started,” can be had for around $100. Beyond that and requiring even less overheard, equipment and preparation lies a new world of app-based, live streaming networks like Meerkat and Periscope, which can transform a person into a personality in an instant.

At the same time, the local has become global, once upon an old media time, a politician on tour or a musician through town might give a few words to a newspaper or radio station, whose area of distribution you could map in fading concentric circles; cable access was available only regionally. Published to the Web, all such material is (theoretically) equally available, everywhere.

Above its other goods, more than the information, the comedy, the confirming us in our opinions, that sense of presence is what makes talk so addictive and electrifying. We all want to be heard. It can seem narcissistic, this compulsive sharing, this shouting into a maelstrom of shouting voices, and, yes, there are those who only want to hear themselves talk. But they are what we might call the extremely vocal minority; mostly it is a matter of the message in a bottle, which we are sending out or looking to find, each on our island. It says, “Hello out there. I am here.”

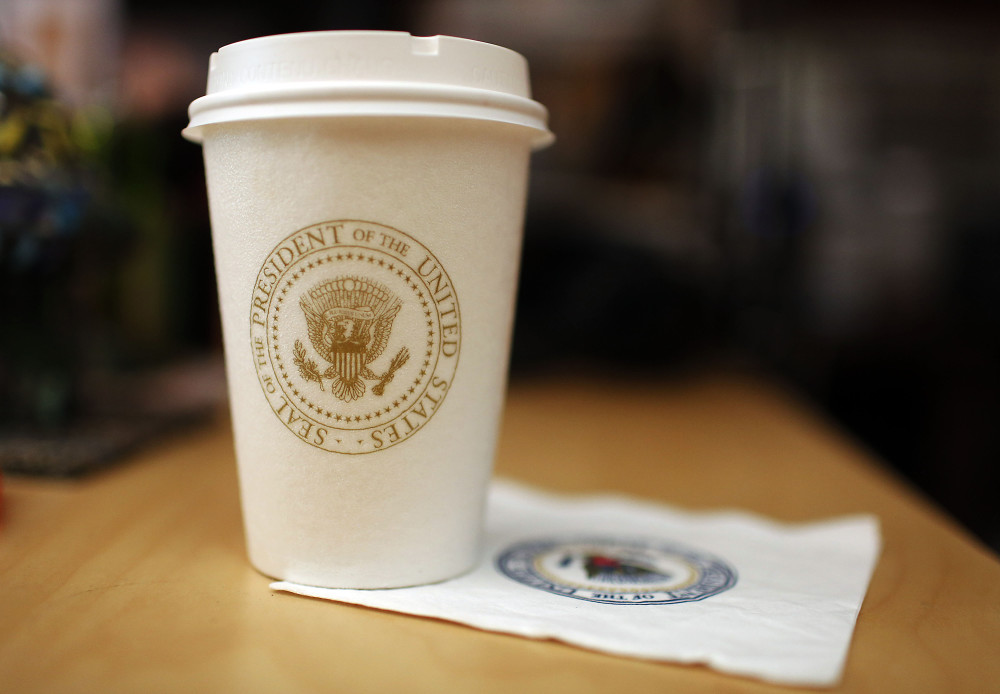

What radio was to Franklin D. Roosevelt, the talk show has been to Barack Obama, and not just the “The Tonight Show” and “The Daily Show,” where he saluted the departing Jon Stewart last week; he’s also spent an hour with Marc Maron and earlier in the year sat down with three YouTube creators; he also appropriated the cable-access-inspired “Between Two Ferns With Zack Galifianakis” to pitch Obamacare to the kids. He’s a man who likes to talk, and can, and knows how to suit himself to the occasion without losing himself in it: He caught the “Two Ferns” passive-aggressive-ironic tone perfectly. Future presidents will all have to reckon with the territory he’s opened.

This world, which is wide and deep, plays by the old punk/new wave rules; it’s an assault on or at least an end run around the citadel of big, moneyed media, a cheap-in-a-good-way, DIY, live-in-the-moment-for-the-moment way to get in the game. As with punk, the size of the audience is secondary to the intensity of its dedication, the sense of shared interest and common cause, it doesn’t take a million fans to make a star, and you don’t have to be a star to stream like one.

Some of these creators, to use the favored YouTube word, do have a million fans, or millions of them. This weekend in Anaheim, Calif., VidCon took place, a conference for online video makers. It was founded in 2010 by Hank and John Green, known as the VlogBrothers and whose own highly appealing, highly verbal and highly mature seriocomic YouTube channel has 2.6 million subscribers and whose subjects range from “Understanding the Financial Crisis in Greece” to “What Boys Look for in Girls.” (John Green is also the author of the young adult novels “The Fault in Our Stars” and “Paper Towns,” whose film adaptation was released Friday; Hank was one of the YouTubers who interviewed Obama.)

In addition to the ease and democratization of distribution, the new models offer freedom, freedom from formats, freedom from time and, perhaps most important, freedom even from success.

On satellite radio, out of the way of the FCC, Howard Stern, always an interesting if at times highly juvenile personality, has matured, if that’s the word, and it probably isn’t, into a first-class interviewer who inspires a more than usual amount of openness in his guests; Marc Maron, similarly motivated, follows his curiosity into dark corners on his “WTF” podcast, an encyclopedia of modern comedy practice. Even Larry King has profited from a move to the Internet; he is more relaxed there, on his Ora TV program, which lets him be weirder and more self-revealing than did cable TV.

Pretty much everyone is here

Also going Webward have been Jerry Seinfeld, whose “Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee,” has grown from a daffy concept to a consistently revealing show about comedy (much of the talk in the online world is about comedy, is comedy itself); William Shatner with “Brown Bag Wine,” in which wine is tasted; and Steve Buscemi, whose “Park Bench” is a roving, mostly alfresco interview show with a light, fictional through line. “Community” creator Dan Harmon has been unburdening himself all over his “Harmontown” since 2012.

There are the storytellers and lecturers, single voices speaking directly to the listener/viewer on public radio series like “The Moth” and “Snap Judgment” and many segments of the influential “This American Life,” and innumerable YouTubers and TED talkers. And there are the conversationalists, who speak to each other in your presence, and may be combative or congenial, rank strangers or best pals. They may be as organized as the public-radio news series “Wait Wait … Don’t Tell Me!” (in the old current events panel show of “Information Please”) or Paul Scheer, June Diane Raphael and Jason Mantzoukas’ “How Did This Get Made?,” in which bad films are taken apart before a live audience, or may just be a bunch of friends passing the time in your presence, jamming.

You can pair your passion, or any noun, really, with the word “podcast” in a Google Search and get interesting results: podcast plus fruit (“The Fruit Nut”), podcast plus hair (“Splitting Hairs, the Hairdressers’ Podcast”), podcast plus energy (“The Energy Gang”). There are podcasts and vlogs for fans of black metal, for Disney fans, choir masters, ham radio enthusiasts (“Solder Smoke,” where you can learn what Bill thinks about the BITX40 with Yaesu filter) and farmers (“Chicken Thistle Farm Coopcast,” where subjects include “capturing a honeybee swarm, annoying broiler chickens and a pre-farrowing pig”).

Also feeding this mighty river of speech is a proliferation of live-event panels, streamed or archived for at-home viewing, each creating a kind of pop-up talk show for the space of an event. Indeed, the idea that a popular television show exists on its own, as a self-contained, indivisible object, is pure 20th century thinking. The show perhaps will be followed by another show in which people will sit around discussing what just happened, as “The Talking Dead” follows “The Walking Dead.” Older shows get a second-stream second life as well, as with Kumail Nanjiani’s “The X-Files Files” or Kevin Smith’s new “Frasier”-themed “Talk Salad and Scrambled Eggs.”

Where you watch dramas and sitcoms as through a window, talk brings you into the room, gives you a seat at the table, a desk in the classroom; it’s collective. You are addressed, “Ladies and gentlemen,” “Nation,” “Friends” and especially “You guys”, and though no one will hear you answer back, usually, a connection is implied, a community. And sometimes you can actually pitch in; your letter might be read on air, or online, or your tweet; they might take your call.

It is possible, of course, to express yourself without speaking, but talk is what literally connects us, where the voice in my head meets the voice in your head. It’s the first thing you hear, the human voice, even before you’re out of the womb and into the world.