By Heidi Stevens

Chicago Tribune.

I’m reading a lot lately about the importance of helping children find their voices.

They need to feel heard and understood within their families so that they learn the power of expressing themselves authentically. Speak up. Be clear. Don’t shrink.

I like this advice, particularly in the face of statistics about girls not raising their hands in class and boys swallowing their feelings to save face in front of pals, and kids, all of them, struggling to find their way online, where social media can be a cruel and unusual place.

One psychologist told me to think about my kids as adolescents facing pressure to smoke pot. Do I want them armed with their own voices and the ability to wield them? Or afraid to speak up for fear of rocking the boat?

The former. Without question.

But we’re embarking on a whole bunch of together time now that school’s out. And my kids’ voices are saying things like, “I don’t want to go to baseball. Why can’t I just watch videos of baseball?” And, “Ketchup is too a lunch.”

We’re all set on expressing ourselves authentically at my house. The challenge is how to greet the expressions that make me want to get lost in a rain forest.

(I don’t really want to get lost in a rain forest. I would miss my kids desperately, and I like to snack every couple of hours.)

The real challenge, then, is deciding which of the various demands, requests and pleas to give in to and which to bypass.

Some are easy. No, you can’t open the birthday gift we’re bringing to your friend’s party. No, you can’t just open it a little bit.

Others are more vexing.

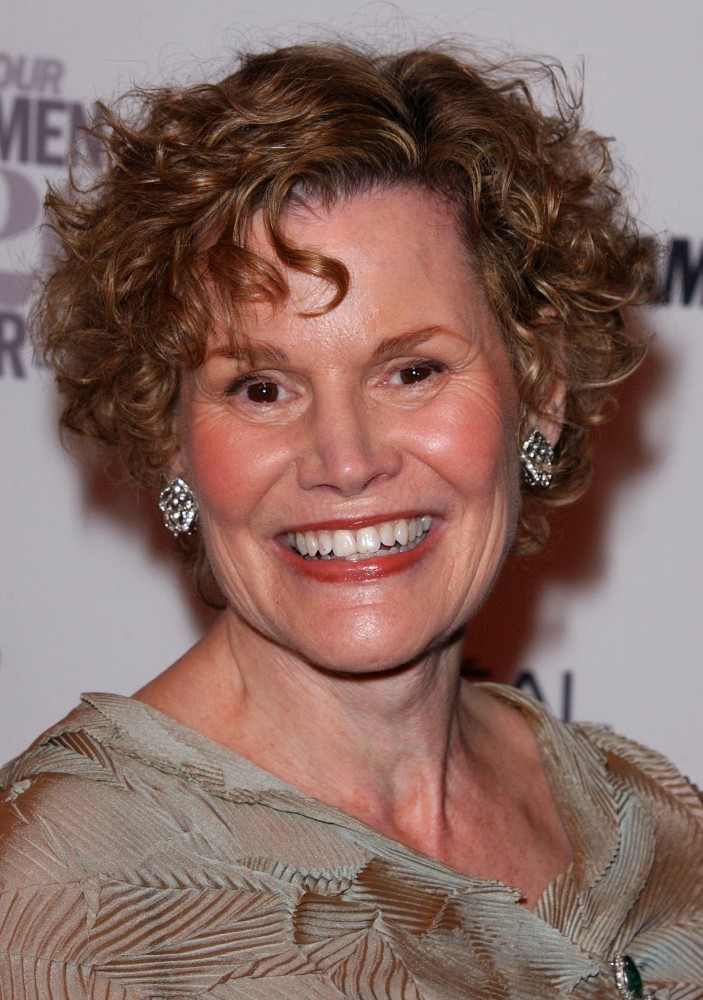

For the 800th time in my life, I find myself turning to Judy Blume for wisdom. She was in town recently for the book tour of her new novel, “In the Unlikely Event” (Knopf), the story of three real-life plane crashes in Elizabeth, N.J., during the winter of 1951-1952.

I interviewed her at the Chicago Humanities Festival, and we discussed talking, really talking, to children. Blume has spoken in other interviews about her desire to deal honestly with children, which is the first step in teaching them to deal honestly with others (and themselves).

“When I’m writing I’m never trying to teach anything, maybe I’m trying to illuminate,” she told Bazaar magazine. “I have always felt that my responsibility as a writer is to be honest.”

She didn’t witness that honesty as a child.

“Adults kept secrets from kids,” she told me. “No adults, parents or teachers at school, ever talked to us about what was going on in our community.”

Even when three planes crashed in the center of it.

I have no desire to return to an era that erected barriers between kids and their parents, that reinforced the notion that kids should be seen and not heard. But it’s challenging to raise kids who speak up.

Blume’s children’s books, “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret,” “Blubber,” “Freckle Juice” and dozens of others, do a lovely job of capturing children’s voices and crafting adults who deal patiently with them.

Since the interview, my kids and I have been staging nightly readings of “Superfudge,” the story of Peter, his younger brother Fudge and the lousy hand they’re dealt in the form of a baby sister, Tootsie.

Fresh on the heels of the baby news, the parents announce the family is moving to New Jersey, where Dad will take the year off to write a book.

“A book?” Peter says.

“That’s right,” Dad answers. “On the history of advertising and its effect on the American people.”

“Couldn’t you write something more interesting?” Peter asks. “Like a book about a kid who runs away because his parents decide to move without asking him first.”

“Sounds like a good story,” Dad says. “Maybe you should write it yourself.”

Brilliant, right? Humor intact, Dad manages to hear Peter and weigh his comments without resorting to shaming or frustration.

No marketing campaign to bring Peter around. No scolding for speaking to his father that way. No parental guilt for wrecking their son’s life.

It’s my model for the summer. Humor intact. Frustration at bay. Rain forest a million miles from my mind.

Kids need to find their voice, but sometimes that voice wants ketchup for lunch